The Lost Souls of Glen Quaich

Today, I’d like to give you a taste of what it’s like to learn English in Perthshire with us, on an English immersion holiday.

It’s probably not what you are expecting.

We share all kinds of Scottish culture with you, and sometimes that’s pretty dark.

Today’s blog is about Loch Freuchie, the ‘Heatherly loch‘ – and its lost, displaced people.

It’s also about the wildlife clearances and displacement which continue under contemporary landowners.

Read on for a taste of Scotland, and immersion into English language and culture.

Culture-Led English Learning

Learning about the culture of the place you take your English immersion course is an important part of a language-learning holiday.

At Blue Noun English Language Hub, we give you different ‘lenses’ to learn English through.

Learning English with Scottish history is a powerful one.

Scottish history is fascinating.

It’s also the story of the people you are visiting and the language you are learning.

“The Highland Clearances were a devastating part of the history of Scotland. For many, it changed not only their way of life but also shaped the rural future of Scotland. Many villagers suffered at the hands of their landlords and tacksmen and fought a desperate struggle to find a new life. Others managed to prosper in a new life that never saw them return to Scotland again.” (1)

Loch Freuchie and the Highland Clearances

Few houses remain visible: as they were made from the land, it would have quickly reclaimed them. Each of the settlements you walk past once had around 10-15 crofts, built of stone, clay and wattle or thickly cut turf. The roofs were thatched in heather, broom, bracken, straw or rushes. Some would have also had also a mill.

Each housed 10-15 families.

What Happened to the People of Glen Quaich?

Most of this development dates from the early 1800s – as a result of the first Marquess of Breadalbane moving Highlanders from his estate around Loch Tay in order to implement new farming and tenancy agreements. (Similar economic and agricultural change was becoming widespread across Europe). This first wave of displaced families did not remain in Glen Quaich for long. In the early 1800s, around three hundred crofters voluntarily left the glen to resettle in Canada. (2)

An Over-Population Crisis

There was huge hardship and suffering and a succession of bad weather and harvests resulted in famine across the Highlands.

An Ulterior Motive

Younger sons of Highlanders had always had to leave home to seek their fortune elsewhere – as the land simply could not support them.

The awfulness of the Highland Clearances was removing an entire stock of people. (2)

All across the Breadalbane Marquisate (as across huge swathes of the Highlands of Scotland), houses were burned, walls levelled and the fields turned into open moorland grazing for blackface sheep. (2)

“Next to go was the entire population of Glenquaich, a lovely heather clad glen running inland from Loch Tay to the hamlet of Amulree, and where over 500 people lived. The evictions were carried out before the houses were set alight”. (2)

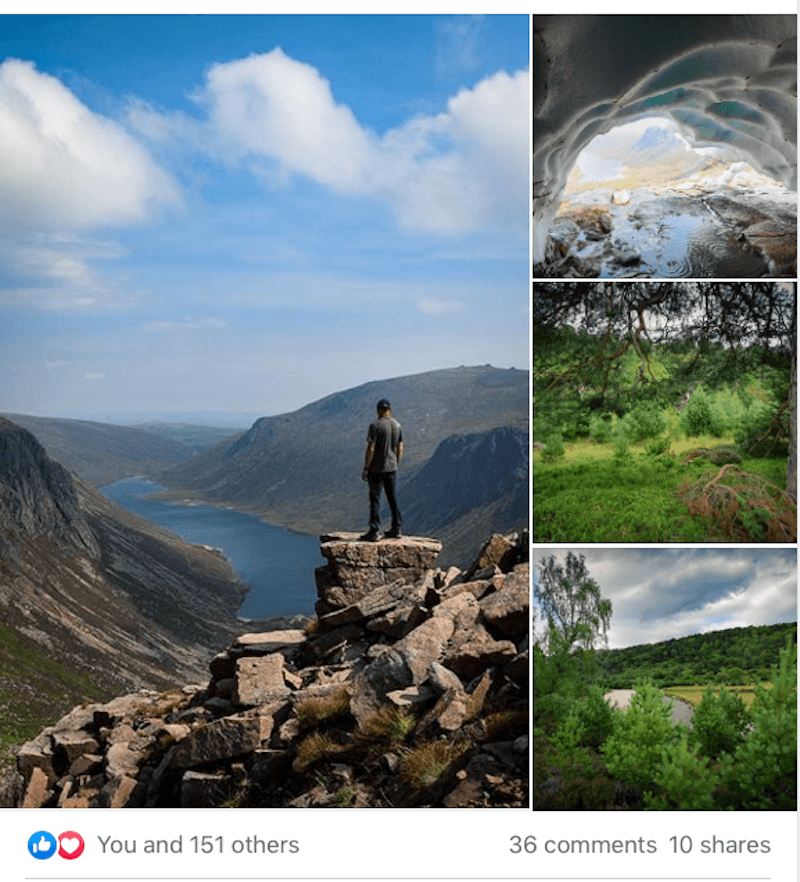

Discover a Changed Landscape, when you Learn English in Perthshire

By 1850, out of 3500 people on Loch Tayside, only 100 were left (2)

The Next Big Change – Hunting Estates

The Land Grab Continues

“The half-dozen native white-tailed eagles recently released on the Isle of Wight required mountains of paperwork. To throw out a few thousand non-native pheasants requires no paperwork at all. In fact, to throw out 47 million pheasants requires no paperwork at all. You don’t have to be much of an ecologist to think that might be a bit wrong.” (4)

“Figures suggest that almost one fifth of Scotland is given over to driven grouse shooting and yet if Scotland’s economy were the size of Ben Nevis this industry’s contribution would be the size of a small banjo”.

Learn English in Perthshire

The Lost Souls of Loch Freuchie

When we use numbers and statistics to give a sense of scale, it’s immediately depersonalising: we know this when listening to the figures of COVID-19 creeping ever higher.

“After the Breadalbane evictions began in 1834 more and more families from central Perthshire began to emigrate . They left with great sadness. The story of Anne Menzies is typical. She was born at Shian, Glenquaich in 1839. Her father was a local school teacher who also had a small croft. Out of this he had to provide the Marquis with two cartloads of peat, so many skeins of wool, so many pounds of butter and cheese, and £16 rent every year. Anne’s family were forced to emigrate in 1842 and sailed from Greenock on the Clyde. The voyage was long and stormy and the ship was three times blown back to the Irish coast. Every one on board did their own cooking and ate their own supplies. There was much sickness and many died. Cholera was the scourge on the emigrant ships and over 20,000 victims of the ship-borne disease lie buried at Grosse Island, Quebec.” (2)

“These are the rarities in human history, the places from which we’ve retreated”.

Kathleen Jamie, Findings, 2005

The Scottish Landscape in the Age of COVID

“Beware that this behaviour (and indeed this pandemic) becomes the latest excuse to close more of Scotland off from its own people” (6).

Learn English in Perthshire – with Culture-Led Tourism

Our language guests don’t just see Perthshire’s beautiful Highlands.

They learn that our ‘bucolic’ Highland landscape is not only shaped by hunting estates – it is scarred by them.

The empty hills we now see – and celebrate as ‘Scottish landscape’ are far from ‘natural.’

Indigenous wildlife suffers in competition and forced proximity (and is often persecuted for its proximity ) to game.

Even our own town of Crieff has a deep divide between the community members who benefit from the wealth brought in by estates – and the rest who are excluded from their own landscape because of them.

When you learn English with us in Scotland, we don’t just give you tours of pretty places. We share information about the history and politics of place – and it’s not a lecture, it’s a conversation about how we can imagine better futures, with the skills, expertise and imagination of our English language guests.

Our English language hub is here for English learners seeking genuine, interesting cultural exchanges.

Glen Quaich and Lock Freuchie.

The traditional view of ‘beautiful’ Scotland, with barren hill and ruinous cottages: to learn its history and ecology is to learn that this landscape has huge cost.

Our landscape contains the story of its people – all those who lived on it and from it and fought for it. For so many reasons, now more than ever, we need to listen.

Thank You, Historians and Eco Warriors!

How can our love of Scottish history help your English?

Learn more

Further Information

English Practice Exercise

Describe a place or space which represents loss. What does it look like now? – How does it represent loss. Mention if it is deliberate (like a memorial) or a result of a change (like space where a building once stood

Choose between using the passive voice (the land was cleared to make way for sheep) when the agent isn’t important, and the active voice (the Marquess of Breadalbane cleared the land, to make way for sheep) when agency is important to the message.